A tokenizer’s goal is to split a text in subpart in order to input these subpart in a model.

Splitting a text can be done at a sentence level (each sentence is a subpart), at a word level (each word is a subpart) or at a character level (each character is a subpart). It can also be done at intermediate levels.

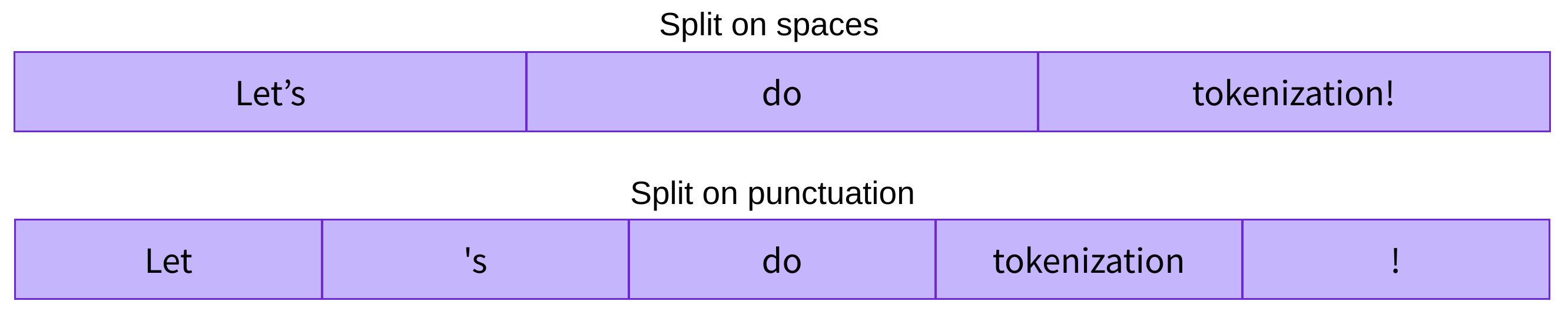

A word level tokenizer will split a text in words. The split can be done using the spaces or using punctuation.

Each word gets assigned an ID, starting from 0 and going up to the size of the vocabulary. The model uses these IDs to identify each word. These IDs are then used to map to a vector representation of the word.

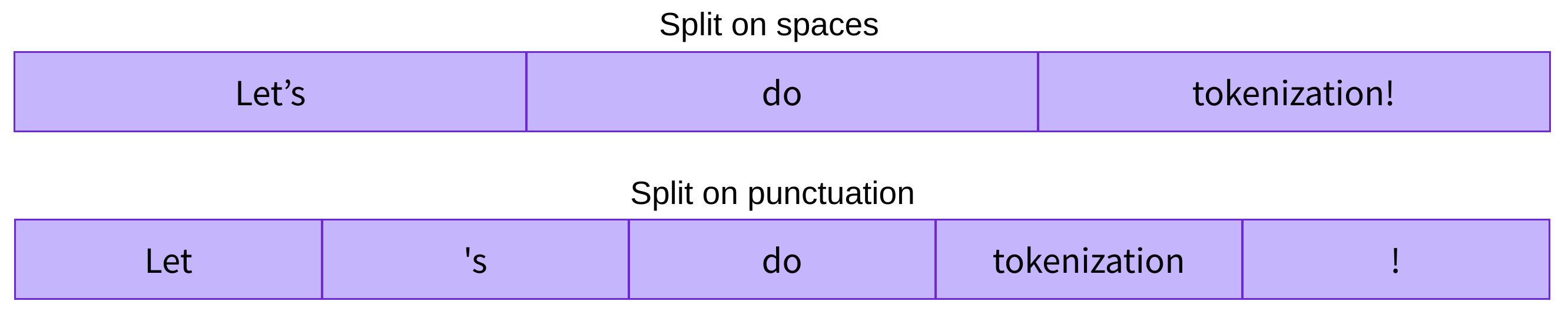

Character-based tokenizers split the text into characters, rather than words. Some questions also exist concerning how to deal with punctuation.

Each characters (letters, punctuation, numbers, special characters) gets assigned an ID starting from 0 to the size of the number of characters. These IDs are then used to map to a vector representation of the characters.

The hidden layer \(h\):

Subword tokenization algorithms rely on the principle that frequently used words should not be split into smaller subwords, but rare words should be decomposed into meaningful subwords.

For instance, “annoyingly” might be considered a rare word and could be decomposed into “annoying” and “ly”. These are both likely to appear more frequently as standalone subwords, while at the same time the meaning of “annoyingly” is kept by the composite meaning of “annoying” and “ly”.

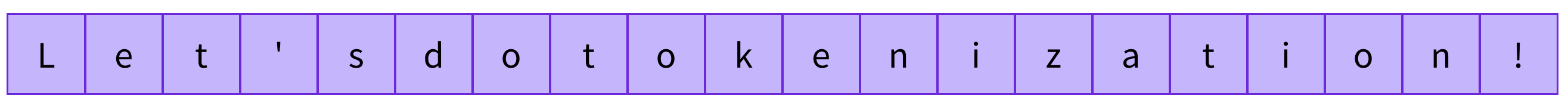

Here is an example of subword representation where the

Each subword gets assigned an ID starting from 0 to the size of the number of subwords. These IDs are then used to map to a vector representation of the subwords.

Note that every characters are kept as subwords to insure that every unseen words have a representation.

(from Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) on Hugging Face)

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) is a subword tokenizer.

BPE relies on a pre-tokenizer that splits the training data into words. Pretokenization can be as simple as space tokenization or more complex pre-tokenization such as rule-based tokenization.

After pre-tokenization, a set of unique words has been created and the frequency of each word it occurred in the training data has been determined. Next, BPE creates a base vocabulary consisting of all symbols that occur in the set of unique words and learns merge rules to form a new symbol from two symbols of the base vocabulary. It does so until the vocabulary has attained the desired vocabulary size. Note that the desired vocabulary size is a hyperparameter to define before training the tokenizer.

As an example, let’s assume that after pre-tokenization, the following set of words including their frequency has been determined:

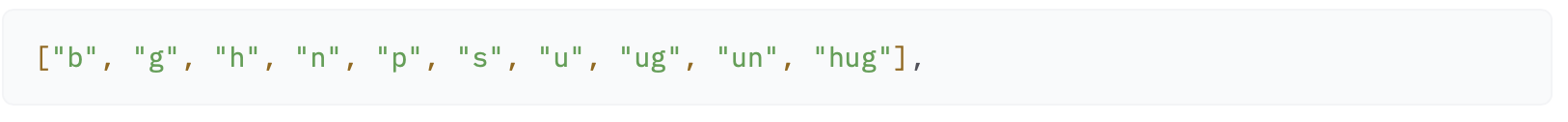

Consequently, the base vocabulary is [“b”, “g”, “h”, “n”, “p”, “s”, “u”]. Splitting all words into symbols of the base vocabulary, we obtain:

BPE then counts the frequency of each possible symbol pair and picks the symbol pair that occurs most frequently. In the example above “h” followed by “u” is present \(10 + 5 = 15\) times (10 times in the 10 occurrences of “hug”, 5 times in the 5 occurrences of “hugs”). However, the most frequent symbol pair is “u” followed by “g”, occurring \(10 + 5 + 5 = 20\) times in total. Thus, the first merge rule the tokenizer learns is to group all “u” symbols followed by a “g” symbol together. Next, “ug” is added to the vocabulary. The set of words then becomes:

BPE then identifies the next most common symbol pair. It’s “u” followed by “n”, which occurs 16 times. “u”, “n” is merged to “un” and added to the vocabulary. The next most frequent symbol pair is “h” followed by “ug”, occurring 15 times. Again the pair is merged and “hug” can be added to the vocabulary.

At this stage, the vocabulary is [“b”, “g”, “h”, “n”, “p”, “s”, “u”, “ug”, “un”, “hug”] and our set of unique words is represented as:

Assuming, that the Byte-Pair Encoding training would stop at this point, the learned merge rules would then be applied to new words (as long as those new words do not include symbols that were not in the base vocabulary). For instance, the word “bug” would be tokenized to [“b”, “ug”] but “mug” would be tokenized as [“

As mentioned earlier, the vocabulary size, i.e. the base vocabulary size + the number of merges, is a hyperparameter to choose. For instance GPT has a vocabulary size of 40,478 since they have 478 base characters and chose to stop training after 40,000 merges.

See:

Byte-level BPE is a subword tokenizer. Byte-level BPE is similar to classical BPE but is based on byte representation.

A base vocabulary that includes all possible base characters can be quite large if e.g. all unicode characters are considered as base characters. To have a better base vocabulary, GPT-2 uses bytes as the base vocabulary, which is a clever trick to force the base vocabulary to be of size 256 while ensuring that every base character is included in the vocabulary. With some additional rules to deal with punctuation, the GPT2’s tokenizer can tokenize every text without the need for the

See:

Unigram is a pure probabilistic subword tokenizer based on the log-likelihood of subword appearances. It starts with a large vocabulary and progressively delete symbols that lead to the smallest increase of the loss (log likelihood).

Unigram removes \(p\) (with \(p\) usually being 10% or 20%) percent of the symbols whose loss increase is the lowest i.e. those symbols that least affect the overall loss over the training data.

Unigram saves the probability of each token in the training corpus on top of saving the vocabulary so that the probability of each possible tokenization can be computed after training.

For a word \(x\), we define its set of all possible tokenizations as \(S(x)\). The for words \(x^{(1)}, \ldots, x^{(n)}\) of the training data the overall loss is defined as:

\[l = - \sum_{i=1}^n \log \left(\sum_{s \in S(x^{(i)}} P(x)\right)\]Where:

The assumptions that each subword occurs independently is done here.

The probabilities of occurence of each subword are computed using their number of occurence in the training data such that \(\forall j, x_j \in \mathcal{V}, \sum_{x \in \mathcal{V}} P(x) = 1\). This mean that the sum of probability of every possible tokenization for an element of vocabulary \(\mathcal{V}\) is always 1.

Because Unigram is not based on merge rules (in contrast to BPE and WordPiece), the algorithm has several ways of tokenizing new text after training. As an example, if a trained Unigram tokenizer exhibits the vocabulary:

“hugs” could be tokenized both as [“hug”, “s”], [“h”, “ug”, “s”] or [“h”, “u”, “g”, “s”]. So which one to choose? Unigram saves the probability of each token in the training corpus on top of saving the vocabulary so that the probability of each possible tokenization can be computed after training. The algorithm simply picks the most likely tokenization in practice, but also offers the possibility to sample a possible tokenization according to their probabilities.

See:

WordPiece is a subword tokenizer.

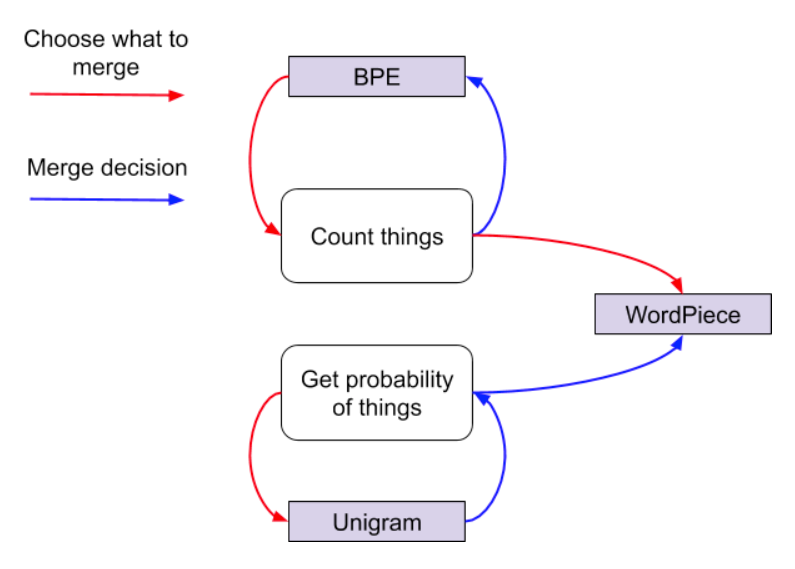

WordPiece is based on the likelihood of subword appearances. It merges subword if the result of this merge has the highest increase of likelihood. But it will try only subwords that have the greater prior ie the larger number of counts.

The main difference with BPE is that it does not only look at the count of appearances of the merge but also the count of appearance of the two subwords. The difference with unigram is that it will not only look at the increase of likelihood but will also use the count of appearance.

WordPiece is not a totally probabilistic model as it chooses potential merge based on the count (such as BPE) but then decides which subwords to merge based on the likelihood.

For example if:

Then WordPiece would rather merge ‘a’ and ‘b’.

See:

SentencePiece is a subword tokenizer.

SentencePiece is the only subword tokenizer that does not require pre tokenization.

It has to different implementation, one based on BPE and the other based on Unigram. Both of these implementations uses some tricks to improve the based tokenizer:

Its main advantage is that it can be trained directly using raw sentences. Also as it encodes the spaces it can explicitly be decoded. For example:

See: